A conversation between Anotnio Pizzo and me (the self-confessed Scheherazade) in 2006, formerly published by Antonio as Identity, Transformation, and Digital Languages.

motiroti is a London based international arts organisation founded by Ali Zaidi and Keith Khan in 1996. Zaidi describes himself as Indian by birth, Pakistani by migration and British by chance. Together with his art companion, he has been working with traditional art craft and new digital media in public events and performance. They grew steadily during the years, and were commissioned to design the Commonwealth Section of the Queen’s Jubilee Parade in London on 2002. Now they are a well known art organization and, after Khan left in 2003, Ali Zaidi leads the company as its sole artistic director. His work has always been about identity and cultural displacement, confronting a world struggling against globalisation. The way he approaches art, he blurs the boundaries between films, theatre, performance, and focuses on the communality of the experience. Most of the time he uses digital technology, bringing out what one could call digital communal performance. I meet him on 15th August 2006 in his studio/office in Islington, London. The conversation concerns two main projects (Alladeen and Priceless).

Antonio Pizzo First time I saw your work Alladeen in 2003 on the main stage in Barbican. Although foremost I was interested in the use of digital multimedia, soon after I was captured by the story, the strong bond between past and future. How did you end up with the idea of that show?

Ali Zaidi Alladeen was a collaborative project between motiroti and The Builders Association, and it stemmed from mutual respect and fascination for each other works. The Builder’s Association works with digital technologies, they often using real stories, and then they dramatise them. Usually they tend to work with a combination of recorded and live media. Naturally there were aspects hidden away but you could see the trailing wires, the cameras and you could see what the camera saw. What made me more connected to their work, rather than the “new technologies”, was that audience are often able to see things from at least two different perspectives: one that was staged out and performed, and another from the point of view of the live cameras on stage. My personal work and the projects for motiroti, since 1991, have mainly been using the familiar form, but then within that sense of familiarity, I interweave the new, the exciting and the unexpected.

What was the work that brought you to join The Builders Association?

Moti Roti Puttli Chunni, our first theatrical Bollywood musical venture in 1993 was the trigger for it all. It was a lush, populist bi-lingual production part film part live performance on stage. Marianne Weems (the founder of the Builder Association) saw it whilst she was a dramaturge with the Wooster Group. Later she formed her own company, and while visiting New York, we saw Faust directed by her, and later saw Jet lag at the Barbican in 2000. We really liked it. A mutual friend & dramaturge, Norman Frisch, brought us together. We came up with the idea of collaboration. Then the question was what would be the ground of our collaboration? There, we strongly stressed our interest for cultural hybridism. Myself and Keith (co-founder of motiroti), were often seen as an “Indian” and motiroti perceived as an “Asian” company. Having played within and beyond those cultural genres we felt it was time to play out ‘cultural fluidity’ on an international stage.

Working with populist stories, which did not need re-telling, was on top of our list and stories of transformation mutually excited both the companies. None other looked as transformative as Aladdin. Also because because this story is a curious mix and match of geographies. It was never a part of 1001 Nights. It is believed that Aladin and Ali Baba are ‘orphan tales’ added by Antoine Galland in the process of the translations. We were interested how stories travelled different continents via the silk-route, paralleled with ‘new technology’ brain-drain-route flowing from India through the UK into the Silicon Valley.

While we were considering all these options and trying to find a through line to interweave the historical and the contemporary, New York Times published an article about Call Centres in Bangalore. Typical of American media, it scandalised the idea that the person on the other end of the phone, “this is Rachael how may I help you…” is not Rachael at all. The article highlighted the plight of detachment/displacement that technology can create. What is the identity of a person speaking on the phone? How we deal with the different identities and its concealment through displacement? We were seeking just this sort of a contemporary hook to hang our Alladeen story! The voice became the signifier! We were excited and challenged by the possibilities this contemporary phenomenon presented. How could we begin to tell the story from the other side? Therefore, why booked our flights. Marianne Weems, Keith and I – the creative collaborators and Penny Andrews (motiroti producer) flew to Bangalore from a ghostly empty Heathrow in the week following 9/11. On our flight back Bush had launched attack on Kabul!!

For how long did you stay in Bangalore?

Our first research trip lasted eight days. Lots of visits and meetings were organised before hand. There were two distinct kinds of services provided by these call centres. A medical transcription service, sent across mp3 files down the line; doctors in US talking into the Dictaphone, call centre staff listened to, transcribed, and sent back immediately. The other service was what New York Times alluded to. We met two big companies, one that had clients like hotels, car rentals, banks, telesales, mobile phone networks. The other company specialised in IT support. IT support team could be themselves and used their own names with pride because ‘Indians are clever people and they know how computers work’!

However, in the other case, people are given American names, and are told never to reveal their true identities or location. The staff went through extensive training of ‘idioms and annotations’ to neuter their mother tongue. The training manuals were amazing, they presented American cultural stereotypes in bite sized chunks. Like a tourist guide for India would state… an Indian does blah blah blah. … Based on stereotypes these training manuals carefully differentiated between East Coast and Mid West and described in depth how Baby Boomers were different to Gen X as opposed to Gen Y!

Definitely… while watching Alladeen, the documentary interviews were integrated as part of the show, my attention was grabbed by those stereotypes. Audience could get an insight on the American clichés in Indian culture. It was witty because we are not used to that, watching American clichés through an Indian perspective. Usually it happens the other way around where Western culture feeds stereotypes about Asian culture.

We began our trip thinking, “Oh my God… poor hungry exploited Indians! Isn’t this terrible?” Upon meeting and talking to the different people within the call centre industry, a more complex and rounded scenario of cultural “trading” emerged. It seemed more like the staff were actually learning something about another culture in a very remote, yet direct way. After an intensive three months period of training via manuals and TV Soaps, they developed a belief system of American psyche. As they got on the floor taking calls, their over-simplified presumptions were challenged by their personal experience of talking to the “real” Americans in America. Realisation dawned that what had been taught and what they were experiencing, were two different things. This was an absolutely beautiful notion that we had to interweave back into the actual live performance.

Could you be more precise on what is the performance about? Could you outline briefly the synopsis of the live performance?

The performance related to the story of Aladdin, the rags to riches story where “anything can happen”. There are two protagonists: a young woman, a parallel of Scheherazade; a global soul, who belongs in the cosmopolitan world. On stage, she first appears in New York… then in London, and she speaks Mandarin, Spanish, Tamil, Bangla, English, and French. You cannot really place her culturally and she looks like she could be from anywhere. She is hardly ever talking face to face. She is leaving messages even to her boyfriend. In a way, she represents everyday experience of distance whether emotional or physical. She is much ‘removed’ and distant by the virtual tools of communication that connect us.

The second protagonist, a young man, an operator we follow through from a call centre in Bangalore; his days of training, to the time he gets successful, to the point when he moves to London and becomes a manager. The show ends on a rather surreal note; in London, in a Karaoke bar, and nothing is “real” because everyone is acting out something. The singers are miming to songs sung by somebody else. Dancers dancing to the flashing lights of a dance pad. Instead of joy, they are scoring themselves whilst dancing: the guy from Bangalore sits at the bar detached and is on a long distance call to his mother back home. Everything displaced and distant.

In other words, the displacement experienced in the Bangalore call centre is still there, in London too.

Exactly. Because everything is about remote access, or (and it is the same) displacement.

Let us go back to the parallel you have made with the story of Aladdin. The girl is linked to Scheherazade because she is the “starting point” of the plot. In fact, the first time we saw her she is talking to the call centre and that is why we switch to Bangalore and the call centre stories. She is the main storyteller. You have articulated the plot in such a way that the “phone line” looks like the main medium for the contemporary storytelling. In other words, the way we usually share our stories hrough TV or films, you are using telephone lines and mobiles to share your stories. Beside this, there is one more thing that I would like to stress about the relation among the Arabian Nights, Sherazade and the show. It is related with the specific starting point of the show. There we see the girl in the street, outside a Virgin mega store in New York, and we watch the building appearing in front of us with a Flash animation, layer by layer. The idea of layers is very effective, both because the Baroque set design were made with layers of wings and backdrops, and because it is deeply linked with the narrative structure of the Arabian Nights. The whole work is composed as a multi layer storytelling (Scheherazade, telling a story about someone that tells a story about someone… and so on), to such an extent, that you cannot track back the line at all. Overall, the notion of layers is linked with the modern idea of identity. Layers, which is that we are made of. So, because Alladeen was about identity, do you reckon there is a direct relation between the use of digital technologies and the issues about identity?

The digital technology is the vehicle through which to tell the story. The piece was about transformation of people, whilst training, the practical experience of taking calls, the impact of work on their lives and the future they aspired to. It was all together- past, present, and future meshed together. The digital technology allowed us to reveal all this swiftly and with great flexibility. The script was devised from the real conversations we had recorded in Bangalore; it was built around the performers and the improvisation with them. Another aspect was the direct link with the audience. Through the web, we had been asking people to submit wishes to the worldwide genie of the web, and these wishes were incorporated through a dot matrix screen within the set design. Wherever we toured in the world, wishes sent from those particular cities were used. It was a combination of different voices: the recorded ones, as well as the performer’s own, as well as all the samples from the old Bollywood/Hollywood films. These provided a very rich matrix and web of many stories against which you can observe the flux: you, as audience, and only you, had to decide what to believe and what to reject.

I found the idea of showing together the fictional call centre operators (performed by actors) and the “real” one in the documentary footage very effective. It was a sort of “mirror effect”, made more complex by the fact that the “real” ones are actually “acting” (pretending to be someone else). In this mixed realities the audience has to take a position. As audience, I had to make a decision about what was the reality I wanted to believe or, in other words, in which story I wanted to be. From this point of view – so far – I think that the show suggested a kind of new experience to the audience. Within a kind of traditional theatre show framework, my experience was – let us say – augmented. More important, I had the impression that what I was watching was only a single part of the whole problem, of a far more complex issue.

I am fascinated by multiple point of views and most of my work explores ways to create just that. It is very important for me, not only to frame an issue, a particular situation, but also, to look at what is outside the frame.

Moreover, there are such issue as the cultural identity, which you can handle better if you try to define what it is not rather than what it is.

Culture to me is something in continuous flux, ever evolving. I often puzzle over as to how best one can define a culture. Describing it in the past tense creates a singular view. To me, that notion is very Eurocentric, a fossilised view and a lazy stereotype. Identity is a difficult subject. In my case, I have been culturally displaced. I am Indian by birth and later became Pakistani by migration. I felt rather torn between these two countries in war. As a young person when I went to India, they said I had become Pakistani, and vice versa. However, one does not have be scared of change… we are constantly changing. If you look at culture of emigrants, the fear of changing, creates peculiar time capsules. Take the Italian community in foreign lands, they live out of stereotypes stopped in time and get so attached to the “idea” of their culture, they BECOME “more” than that idea.

The cultural cliché is usually produced by the dominant and powerful culture over someone else. Talking about you – and even me as Italian and Neapolitan, could our point of view be possibly different from one of somebody who has lived in a dominant culture (as the English or the American)? Would you believe that UK culture is more self-centred that what we are? Do we have a different awareness of our culture as different? Does identity have a deeper sense in our conscience?

It does and it does not. I am not completely sure. I personally think that the question of identity arises in different ways. If you arrive in a room full of strangers, you would probably think at yourself as “an Italian”. You wouldn’t do that if you were among Italians, even tough you probably would say “I am Neapolitan”… and so on. It is like looking at the big picture and then finding where you belong. That is what is interesting to me. In Cut out, a video triptych, filmed in six different port cities of the world explored urban civilization. Global cities, where cultures are so mixed that recognised brands become the most visible, brands of ‘corporate civilisation’. How do you begin to break away from that? How do you begin to see underneath it all? I do believe that one begins to locate, only by observing the vernacular. Back to your question, about being in the centre or being peripheral, I would like to think that when there is a lot of similarity, we try to pick up a difference that defines us. And we always find a way to create that difference, that uniqueness. We can be English, Indian, or Italian, and sure enough, there are generalisations. In Bangalore as part of the training to understand “Americans”, they had a detailed manual outlining the various designated regional, cultural, and social categories.

At the very same moment, I may say that the only way we perceive the world is through categorization. We need it at the first place, even if we – hopefully – go deeper and deeper in our knowledge. Anyway, the idea of how do we perceive reality, brings us back to the digital culture. Is it a medium? Does it bring a new aesthetic? Literature on digital culture acknowledges two seminal notions: transformation and displacement. Everything that is digital is always on the edge of transformation, being digital means being a stream of numbers processed by some sort of algorithm. Furthermore, digital is also another way on being as virtual, being detached by the material things, being a flux of data. I believe that in Alladeen those two issues were deeply bound, both in the story and in the form you used. In other words, the content and the language in your show mixed perfectly together.

The use of technology for the sake of it doesn’t appeal to me as it doesn’t neccessarily transcend. The bottom line is that technology is a tool to communicate. Look what is happening on the blogs (video blogs, audio blogs). People want to share stories they want to communicate. If essential sense of communication is missing, then it feels like gimmickry. Even if the web is full of porn, business, ads, what is overriding it is the blog phenomenon. Moreover, mostly we do spend a lot of time, talking.

Let us try to bring back the issue to art and performing, leaving aside the sociological questions. For example, do you believe that digital technology has brought anything good and better to your art?

Yes, it has. Like I have got used to my mobile phone, to my refrigerator, I just take it as a way of life. Similarly, digital technology is taking over the analogue. It has its own problematics too especially when you take it for granted. One afternoon, towards the final hectic stages of post-production, working on Priceless, electricity failed. Suddenly everything was gone. Scary! If a satellite isn’t working you are fucked. Yet, the flexibility it offers, the fact that we can communicate with every one in many ways, is marvellous. With flexibility I mean that, for video for instance, if you want to change something you can do that, if you want to transmit it, you do, and you can send it directly to someone’s house, or you can podcast it, you can burn a DVD and post it. In other words, there are a lot of different ways of disseminating the stories and that content. Nevertheless, what is important is the intimacy with which you collate those stories and create the content. The intimacy of process, of working with people. So, whether it is digital technology or not, I do like to get my “hands dirty”. That really gratifies me.

You have stressed the idea of process. This is a core concept for digital culture. The way we can now process the data induced Negroponte to say that medium is no longer the message. That is a sort of sociological point of view. From the artistic point of view, could you say that the digital format, its elasticity, made you capable of recording not only the fixed data but also the whole process, the very nature of the process? I am not talking about recording a video, catching the memories of the process in a clip. You have stressed that your job is not sitting in front of the computer, or writing a text, but rather being with people, engaging people in doing things together. To you, it counts a great deal, all the work that is done before the actual final presentation. Then, it is true that the fluidity of digital technology is a core feature to highlight the fact that there is a project – a process – behind it?

It is possible but is not easy. It is a major concern that drives me to work with the digital.

This was the specific case of Priceless. First, give me an outline of the overall project.

Serpentine Gallery commissioned motiroti, to use as “canvas” the entire Exhibition Road, a principal north-south street in the ‘Albertopolis’. Home to major museums: Natural History Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, and other Royal institutions. Even though it was dream of Prince Albert to bring applied sciences and arts together, over the time they have become so specialised that they don’t talk to each other. They are so specialised within the same institution, departments don’t talk to each other. This is “categorization” gone to the extreme. People, things, jobs, and lives are slotted into such neat and tidy boxes. I wonder where the bridges are? Where is the cross over? I wanted to make visible the ‘barely’ visible and make audible the ‘barely’ audible. So, the phenomenon that interested me most were, Migration, Categorization, and Representation. Not only how the Museums categorise and label their exhibits, but also how did they get those exhibits and objects in the first place. Priceless created multiple perspectives from curatorial and personal point of views. Curators selected objects/ideas priceless to their institutions that were used as triggers for “road shows”/live events for which we inviting people into these institutions.

What do you mean with “live events”?

I wanted to invite people and create road shows, where we (the museums and motiroti) brought experts/artists as facilitators to animate the invited groups of people. I wanted to use the object (for example a jade monkey given by the V&A) as a trigger that brought us in the same space together and to talk about and share things priceless to them and us. People brought their priceless objects and stories to share. It was during these events that we collated our “raw material”, the video and sound portraits. Royal Geographical Society had a list of the provisions that were purchased by Captain Scott for his last expedition to the Artic. Therefore, we used that shopping list as an example and asked people what items/things they would take for their journeys away from home. We mixed those lists together. The hierarchy of Scott’s champagne glasses, jute rugs to Axminister carpets, were placed together with i-pods, sketchpads, compass, or photographs of family that the participants choose to include in their list. Almost giving an insight into why those things are precious to them. Therefore reveals a bigger perspective; you begin to see beyond that showcase where the exhibit sits in the museum. It was about breaking those boundaries and having a broader dialogue . My role was primarily to be able to conceive and create a space for the people to share their objects, stories, and values.

The way you talked about it sounds like all the major things happened before the opening of the actual exhibition.

Exactly!! What people see as an exhibition now is only a residue. It is about displacement and this is really all we have in our lives. We have memories, and they are displaced: it was all about this discontinuous flux of residues, and the digital is able to capture these residues, and this is really beautiful. You can then put it together in a flexible way, so that you cannot only bring people back into an event that happen sometime ago, but you are presenting something else that is mixed with so many other voices. So what you get is a kaleidoscope, multiple perspectives, rather that thinking of it as the only possible final thing.

In fact, the notion of kaleidoscope is seminal within the digital culture, as Janet Murray stressed. The fact that we don’t live any longer in a world with a single point of view. The very nature of our contemporary experience is kaleidoscopic. Nevertheless, within the word “performance” usually we see the notion of living time based event. Now, mostly, when we see a digital performance, we end up watching a video clip. Where is the live event? Even in Priceless, we don’t see any live event going on, even if it was centred around the life of people. So how do you join the lifelessness of a digital video clip with the ‘live’ that we want to picture through it. This strikes me because one thing that has been said about digital media is that in its very nature it is always a live event. In other word, as Brenda Laurel stressed, what happen on the screen is always a live event that happens in front of our eyes. A picture on the screen is a stream of number rendered by specific software in real time.

Theoretically, yes. However, in practice I don’t see it always like it, because even if it is processed, the nature of what is recorded is not changing. Yes, there is a process involved, as well as in the 35mm camera, where there are such a numbers of cogs moving the films. Indeed, digital has the power to be changed: that is what triggers my interest. I remember that when we were doing Allaeen, we met up with an IT specialist from Tata (a big company in India) one of the main provider of software engineers to Silicon Valley. He had a very interesting observation to make, even if it is very kind of “culturally reductive”. He said, “China is a great manufacturing nation in the world because they are happy to repeat a task again and again. Indian music is not written; it is orally transmitted and hence is more fluid. They like to do things, but never in the same way. That’s why Indians are great at developing software much better than any of other cultures”. It can be seen as rather simplistic but I think that there is something of a truth in it. I hate to do the same thing over and over again. I try to look at things in other ways. Presenting the same idea with different refrains is exciting and that relates to layers.

So, your perfect performance would be the one that will change every time you do it.

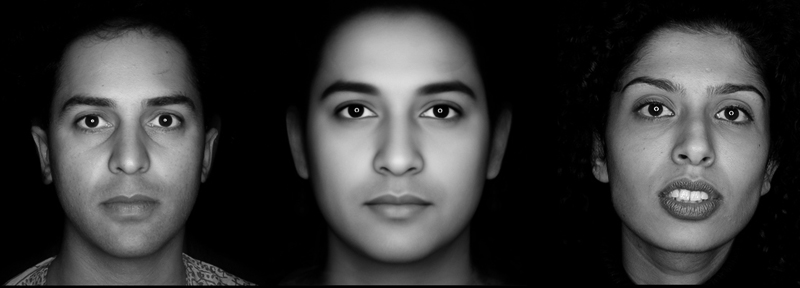

Absolutely. In fact, one of my favourite ever-evolving pieces is Fresh Asian (originally created for Fresh Masaala presented in 2000). The morphed image of a quintessential Asian is continuously challenged by its juxtaposition with the faces from which it was developed. The digitally composed face using a software called morph, sits larger that life in the middle, and then you have changing self portraits of the ‘real’ people. It is an ever-changing piece. It’s going to Lille this year and I know it will be a different piece in its presentation as well as the fact that always new faces are added into it.

Let me go back to your personal career. You usually present yourself as an Artist or an Art Director. So, say that you are lecturing in a college and someone among the students asks you “How do you become an Artist in those digital fields? What do you do in your job? How did you get there?”

Being an artist it is very straightforward because it is about your heart and your passion. Being an Artistic Director is slightly different because it is about having a vision as a starting point and then building the right team around it. Not getting people who necessarily follow your vision, it means getting people who are really passionate about what they do. In the jigsaw of forming a perfect team, when you locate the right passion, where people really believe in what they do, then all fits together beautifully.

Could we bring the subject down to heart? What are the skilled involved?

In Priceless, most the works were conceived as digital interventions going back into the museum spaces. The two key collaborators were Daniel Saul directing the video, and Poulomi Desai working with sounds and creating music. I particularly chose to work with them because they are passionate about what they do; they know their material and tools and are open for dialogue and further have empathy!

I think that in order to be a theatre director, in order to work with actors, beside all the hart and passion we have named before, you must understand drama, be able to read a text properly in its dramatic features. This is a particular skill that you have to develop even if you don’t have to be a writer, a dramatist. The same is with the actors’ side. You don’t have to be an actor but you have to have an insight within an actors techniques, because if you do not know what they are doing how you may possibly discuss, guide them. All those things are – according to me are craftsmanship and technique. So, at this level, being an artistic director in such a complex project as a digital multimedia event, where you deal with so many different skills involved, what is your must-have skill? What you must know to get the best out of them?

You may not have an entire knowledge to be a director, but I find it very useful to have some idea of the tools. For instance, I know very basic editing softwares but I would not edit by myself. Particularly in Priceless, my role as artistic director was to bring an overview, and give my collaborative team, the space to explore. This happened in different stages: having been clear with the brief and communication all the way through the various stages of the process, I allow the space needed for the team to develop things the way they want. Constant peering over the shoulders is not healthy. I created enough of a distance to be objective yet subjective at the same time. Daniel presented and created his ideas, Poloumi created her material. At different stages we met to ensure the individual pieces stood strongly in their context as much as collectively, the integrity was guided by the vision. As a director I created a space for my collaborators to own their aspects to the fullest…whilst still gently and quietly guiding the project – otherwise, why collaborate!?

Would you call yourself a storyteller?

Totally, and I am the self-confessed Sherazade; I go from one story to another. Somehow, all those stories are connected. I digress very often in thoughts and conversations and that is just how I am. This digression is the essence of my kaleidoscope. I feel its called associative thinking 🙂 Different perspectives of people/artists brought together bring out the best. Getting them to share, what it is important to them, so collectively it becomes a richer experience for all of us – as participants and audiences. Within Priceless, even though we had separate pieces constructed for each of the museums, the mobile units on the street told the story collectively. Four video screens became a stylised person – the top screen as the head, two side screens spread as welcoming arms. The head showed portraits of all participants, the arms revealed different words of wisdom, anecdotes, and priceless values, and the base monitor held priceless objects around which the live engagement took place. As a director working in close collaboration (when it works well!) one has to play micro macro continuously. For example, Dan said, at one point, he would have liked to make holes into the buildings alongside the Exhibition Road, so that we could see from the outside inside. As the director, I was able to do that by large-scale projections, embedding the work we created into the very fabric of the bricks. Its about how best can you orchestrate.

Back to the skills, you asked me, I do not know how to acquire them other than practising and learning. You do a job and then you ask what was right and what was not. In this sense, evaluation becomes crucial. It is also important to be able to detach yourself by what you are doing, and get a sort of overview in order to evaluate. One has to think beyond one’s ego and you think of the whole process, and what impact the final work is having too.

There would be any kind of specific education to help being part of a group as yours?

You could be from very different fields: editing, filming, computer graphic, web design, and art… virtually anything involving some sort of creativity. Having a storyteller in you helps. Be curious, be open, stay non-judgemental and keep feeling your emphatic pulse!!

Would you say that your particular role has been better codified in the last decade? I mean that calling yourself an artist you will join a very large category, while, for example, if you call yourself a film director you are addressing a much narrow notion and artisanship. In a more precise notion, can see yourself in as art director of digital performance?

It sounds quite elite to be part of such a special breed. I think all of us we have that capacity. Each of us does several things together. We are the directors of our own lives. However, we can train to develop the discipline of over viewing, a sense of orchestration in your vision, and to know your own capacity. In Priceless, for instance, all the mobile units were my own work; and I had my “hands on” with the graphics in the pedestrian tunnel from the underground. However, the most exciting moment is when I can engage directly with people.

So far, you have stressed the link between being a storyteller and the communal experience. These two concepts are so bound together that it seems that you gather people together as a means to storytelling. I remember the Peter Brook’s point of view: he moved more towards the storytelling experience (with his “magic carpet”) the more he defined theatre as communal experience. Also in your approach, you do not focus on the “ego experience” as storyteller, but rather on the fact that the storyteller is a mean to bring people together: it is not the end but the starting point of the communal experience. Again, the digital experience allows you be a storyteller through people. Your “magic carpet” is the digital environment where all this happen, where you can gather different experiences together. It is a quite peculiar feature even if it is quite blurred, vague.

One of the toughest challenges working on Priceless was the different partners institutions took an eternity to understand motiroti, because they were seeing us either as a film company, or as an educational organisation.

I can understand their point of view because they were approaching you in the same way I did when I asked you about your “professional identity”. Quite the opposite, you are dismantling, undoing, the very idea of professional identity, the categorization of being an artist of a precise breed.

Only now, they have started to e-mail us, thanking and saying that they understand what we were doing; now they could see that aspects of education and learning, as well as art, as well as community work were all inextricably linked together. There was a gulf of difference in our interpretation of the word “community”. There are thousands of communities. Community of people working in the museum; within the museum there is the community of chefs, on the Exhibition Road there is the community of cleaners, etc. I do not reckon there is any sense in selecting people with dark skins and calling them “a community”, or saying that I do community work because I gather together people with from non-EU origins. Why don’t we often re- define, question, and refresh the old definitions? My litmus test is that I always imagine my mother in the audience. I feel redeemed when I can extend her an experience of my projects and feel connected, as well as my 20-year old friends and my broad peer group. Audiences matter a huge deal to me as my work is made of “people” who participate and are also the audience.

There has been or will there be a time for you to be a solo storyteller?

I cannot tell a story on my own. I remember a performance, back in 1995, Wigs of Wonderment, in which we were five performers but the audience met only one performer at time. I may have been seen as a performer, but I used perfumes and smells to cajole my audience to become the performer and the storyteller. I let them smell and talk about what memories those smells triggered: we all have such a great stories. My solo performance Cooked with Love (2004) was created to celebrate 45th wedding anniversary of my parents. There were 45 dishes, 45 ingredients, and 45 guests. Over a slide show, I retold the story of my mother and father, bit of my own, as well as the story of my partner. I was playing the Scheherazade again and again. Once I had done that, the food was dished out and soon enough, tickled the bellies, and animated the people, I took a back seat as they became the performers. I really like the saying, “Let a thousand flowers bloom”. Why only one point of view? The absence of difference becomes a monoculture, and that is boring!

USEFUL LINKS

The Builders Association has recently published their first book Performance and Media in Contemporary Theater. Buy it!!

Marianne Weems and The Builders Association have spent two decades refusing to divide expressive forms into ‘Old vs. New,’ as they invent their astonishing hybrids of live performance and digital media. Jackson and Weems’s book is a record and synthesis of their remarkable work.

(Clay Shirky, author of Cognitive Surplus and Here Comes Everybody)

Download PRICELESS pdf

Download motiroti pdf